THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

HistoryHistory

Vol. 2 No. 7 July 2015

HISTORY

20

A Work

of Art:

Illuminated

Manuscripts

15

Classical Writing:

The Feather Quill Pen

Writing for the

Common Man

Writing for a

New Century

28

34

WHAT’S INSIDE?

HISTORY

EDITor'S

NoTE:

Writing. The history of Writing.

The tools of writing. The act of

writing. The therapeutic, relaxing

nature of writing. Writing is

something which has appealed to me

ever since the very first day I

realised you could use a pen for

things other than drawing stick-

figures on the wall. Even now, I

still remember the first stories

I ever wrote when I was five and

six years old. They were almost

invariably about cats. I don’t

know why this is…cats are curious,

mischievous creatures, and I guess

I was, too. As are all of us when

we’re six years old.

I’ve always loved writing.

Reading about writing, writing

about writing, and writing about

the things I love. And in this

issue I’ll be able to combine them

into a marriage made in Heaven. Or

at least, Heaven on Earth.

Shahan Cheong

We offer both veteran and undiscovered writers the opportunity to get published.

Have something to

COMMUNICATE, or an OPINION to state, wer are your voice!

Want to

join a like minded community in a great project

WHAT’S INSIDE?

WELCOME 05

THE BIRTH OF WRITING 09

CLASSICAL WRITING:

THE FEATHER QUILL PEN 15

A WORK OF ART:

ILLUMINATED MANUSCRIPTS 20

WRITING FOR A NEW AGE:

THE INDUSTRIAL REVOLUTION 22

WRITING FOR THE COMMON MAN 28

WRITING FOR A NEW CENTURY 34

GRAPHITE AND RUBBER:

A HISTORY OF PENCILS 42

CONCLUSION 48

SOURCES AND REFERENCES 52

Welcome to the TAT – HISTORY issue for July, 2015!

One of the most important achievements mankind ever made was the

creation, and understanding of, the written word. From ancient times to

the 21st century, fewer things have been more powerful and important,

interesting and funny, thought-provoking and revolutionary as words. Or

rather, the ability to write them down.

In this issue, we are looking at the history of the written word and the

history and development of writing instruments. If you’ve ever wondered

where writing came from, and how it evolved, and how the tools to create this

wondrous method of documenting human intelligence came from, this is the

issue for you! Let’s nd out together…

The Editor,

Shahan Cheong

Welcome

Ȉ

Ȉ

Ȉ ǡ

Ȉ

Ȉ

Ȉ

Ȉ

Ȉ

Ȉ

Ȉ

Ȉ

To book an appointment visit our website

or call Caitlin on:

0433 319 609

www.inbalancesportstherapy.com

Mobile Service

We come to you!

E

ver since the Stone Age,

mankind has looked for ways

to communicate and record

thoughts, ideas and events to other

people in ways that they might

understand. For centuries, man

has looked for ways to record for

posterity the great events of history

and the small events of the day.

A method for doing this would be

called…writing!

The earliest forms of ‘writing’, of

a sort, were the cave-paintings left

behind by early man. Hand-prints

and crude drawings of animals.

These basic pieces of art, although

they contain no letters, are the

first signs of man’s attempts at

communicating, and recording,

beyond the spoken word. Although

sufficient for conveying a simple

message of fact, painting was not

precise enough to record thoughts,

ideas or complex information.

If the human race was to advance

itself, it would need to find a way

to communicate. It had to learn

how to create symbols which stood

for words, it had to know how to

read these symbols, and how to

communicate using them. It had to

learn how to write!

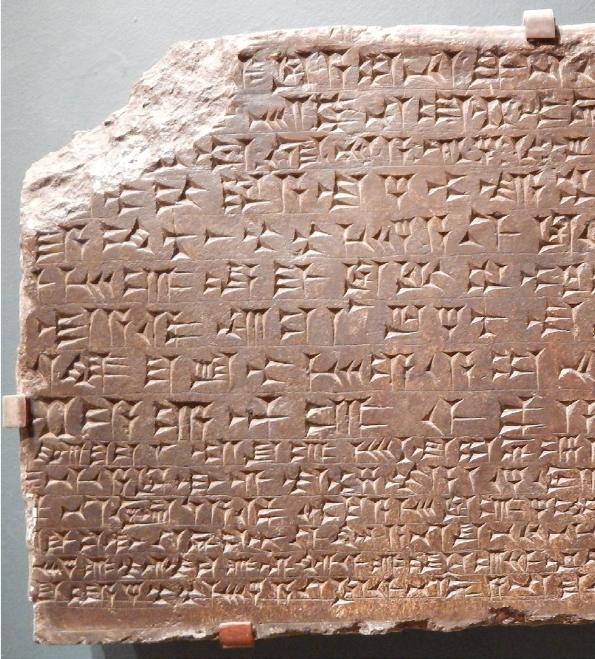

Cuneiform and the First Writing

The earliest form of writing

which most people recognise is

called cuneiform, from the Latin

words meaning ‘wedge-shaped’.

Cuneiform used a reed or stylus

to press triangular, wedge-shaped

indentations into tablets of wax

or clay, in different combinations

in order to represent letters,

sounds and words. Dating back

over 5,000 years, cuneiform was

the written language used by the

Sumerians, one of the first recorded

civilisations, which existed in what

is today, the Middle East.

Created in about 3500BC, by the

2200s BC, cuneiform script had

evolved from simple representations

of thought, or pictographs, to more

complex communications regarding

human emotions, love, honour,

betrayal and religion. About a

hundred years after this came one

of the first serious pieces of written

literature in the history of mankind –

The Epic of Gilgamesh!

The Birth of Writing

by Shahan Cheong

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

9

HISTORY

Ancient clay tablet with

cunei

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

10

The story

about the

King of Uruk

(the capital

city of Sumer,

the ancient

land which

saw the birth

of cuneiform

writing) – the

eponymous

Gilgamesh – is

considered the

first use of a

writing system

to create a work

of literature, or

to write down

an actual story

to share with

mankind for

posterity.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

11

HISTORY

A Picture Paints a Thousand

Words: Hieroglyphics

Cuneiform was the first writing

system of which we know. But from

the start, this wasn’t a one-horse

race. Running alongside cuneiform

was another writing system, which is

probably far more familiar or famous

to us today – Hieroglyphics!

Invented by the Egyptians at

around the same time as cuneiform

(about 3500BC), hieroglyphics were

not letters. They were not even

words. These little pictures and

symbols were in fact syllables. Each

little image represented one syllable

of the Egyptian language. Strangely,

though, the word ‘hieroglyph’

isn’t even Egyptian!...It’s Greek! It

comes from the two words ‘Hieros’

(“Sacred”) and ‘Glypho’ (“Carve”).

So literally – sacred carvings. In

Egyptian, this was translated into

“God’s Words”.

Hieroglyphs remained part of

Egyptian culture for thousands

of years, and along with the

hieroglyphs, the Egyptians also gave

us one of the first writing-tools!

The Stylus and the Reed Pen

Early writing systems, such as

cuneiform and hieroglyphics were

slow and complicated. This was not

aided by the writing implements

of the day, which comprised of

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

12

Egyptian-style

Heiroglyphics

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

13

HISTORY

a wooden wedge stylus to press

into clay tablets (to make the

combinations of wedges that made

up cuneiform), or a reed pen and ink

on papyrus (woven reeds) to create

hieroglyphics.

The problem with reed pens was

that they never lasted very long.

Constant contact with ink (likely to

be made up of plant dyes or soot,

mixed with water) meant that the

tips would soon become too soggy

and weak, unable to hold a shape

properly. This meant that the tip

of the reed would have to be cut

off and reshaped periodically, to

create a new writing-point. For

this, and other reasons, such as the

complexity of writing hieroglyphics

for long periods of time, that newer,

faster and simpler writing systems

had to be developed! Like the

Phoenician Alphabet!

The Phoenician Alphabet

The Phoenicians (a civilisation

from Phonecia, modern-day

Lebanon) created what is widely

recognised as the world’s first

alphabet with symbols or letters

which could be combined in any

number of ways to spell out words

and phrases. Being able to chop and

change letters around, as well as

making them shorter and simpler

than hieroglyphics, made them

faster and easier to write.

Starting from about 1050BC, the

Phoenician alphabet was the new

way of writing. As Phoenician traders

sailed the Mediterranean Sea, their

language and alphabet spread to

the countries that bordered it. The

Greeks adapted and simplified the

letters, as did the Romans who came

after them.

During this time, writing was still a

slow and laborious process. For most

people, writing was still done using

wax tablets, or even stone slabs! For

this reason, writing quickly was not

possible, and any writing with curves

in the letters were also not possible.

For the next several centuries, the

reed pen reigned supreme as the

main writing instrument of the day,

but despite its widespread use, it

had several shortcomings.

Reeds are stiff. If you pressed on

it too hard, it would snap or break.

Reeds wore out easily and had to

be sharpened and reshaped over

and over again. This made them

unpopular, and people were always

trying to find something better to

write with.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

14

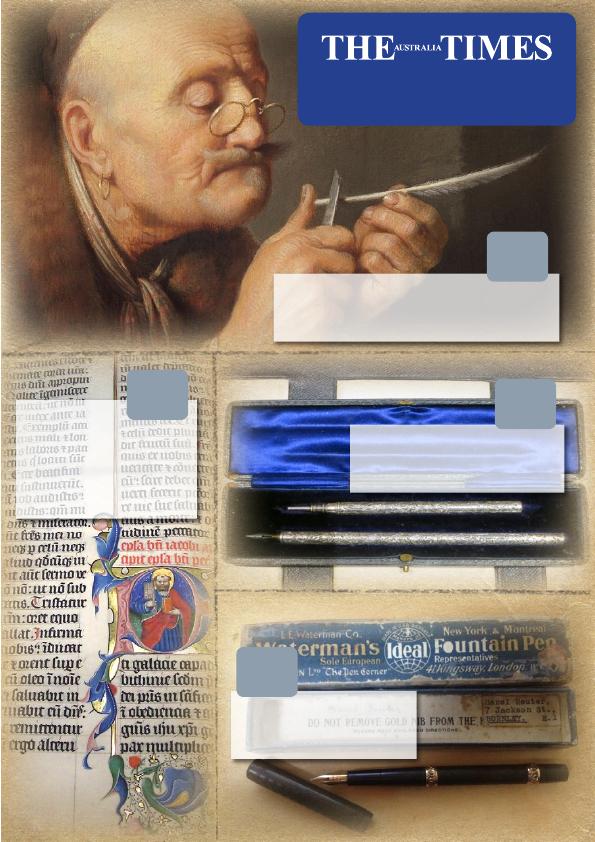

Classical Writing:

The Feather Quill Pen

by Shahan Cheong

After the fall of the Roman Empire in the 400s, reed

pens remained the primary writing instrument in the

Western world, but they also remained unpopular. This

persisted until the 500s, when a new writing tool was

developed – the quill pen!

The quill pen is the iconic writing instrument

of the Middle Ages! From around 500A.D. until

the mid-1800s, we imagine monks, priests,

men of letters, doctors, famous authors and

men of business scribbling diligently away

at their desks with fuzzy, fluffy, fluttery

white quill-feathers, producing line after

line of neat, legible script! Right?

Ehm…sorta.

Sorry to say, but the popular

image of the quill is just that –

an imagination – it almost never

existed in the real world.

During its period of popular

use, a quill was prepared in the

following way:

First, a feather was needed.

A large flight-feather, usually

taken from a goose, swan or

other sufficiently large bird.

Once

the

feather

had

been

obtained

and was

judged to

be in good

shape, the

feather was

tempered –

that is to say,

it was dried and

hardened. This

made it stronger and

meant it would be

more durable. This was

usually done by burying

the feather in hot sand, to

drive out all the moisture

in it.

The popular image of a quill

pen. Although they look very

pretty, quill pens were never

actually produced this way -

it was too impractical in the

long-run.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

15

HISTORY

Once the feather was dry and

strong, the sand was removed and

using a small knife…a pen-knife…the

feather was prepared for use. First

step was to remove all the barbs!

The fluffy, white frilly bits at the

end!

We often imagine that quills were

kept whole, but this was rarely the

case, purely for the fact that the barbs

would get in the way! So writers

making their own pens would usually

just cut them all o, or at least cut o

the majority of them, to make the pens

easier to hold.

Once the quill had been dried and

trimmed, it then had to be cut. The rst

cut at the tip was diagonal. Then two

more cuts to make a triangular point.

Then a fourth cut up the middle to

split the point into two ‘tines’. This last

cut created a channel for ink to ow

along when the pen was being used.

Quills were more popular than

reed pens because they could last

longer, but also because the flexible

nature of the quill point allowed

for different styles of writing. The

different ways that one could cut

the pen-point meant that even

more options were available. This

versatility led to new and more

artistic styles of handwriting, such

as the famous German Blackletter

script, and Uncial and Insular scripts,

widely associated with texts of the

Middle Ages. Producing writing

styles like this would be impossible

without the flexible writing points

of quill pens.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

16

Because of this, it would be

necessary every now and then, to

cut off the worn out pen-point, and

using your pen-knife, cut out a new

point. Over time, the pen would

get shorter, and shorter the longer

you wrote with it, a bit like a pencil.

It’s for this reason that the barbs

(feathery bits) at the end of the

quill were often removed! Because

they served absolutely no practical

purpose whatsoever, they simply got

in the way of your hand when you

were writing.

Some of the most famous and

important documents in history were

written using quills. The American

Declaration of Independence. The

Magna Carta. The Bible. Almost every

text that survives from the Middle

Ages to the 1700s. They were all

written with quills.

For all their advantages and the

dierent styles of writing which they

allowed, quills still suered from

the same problems as the reed pen.

Eventually, the hand-cut pen-point

would lose its elasticity and springiness

as it got more and more saturated with

ink due to repeated dipping.

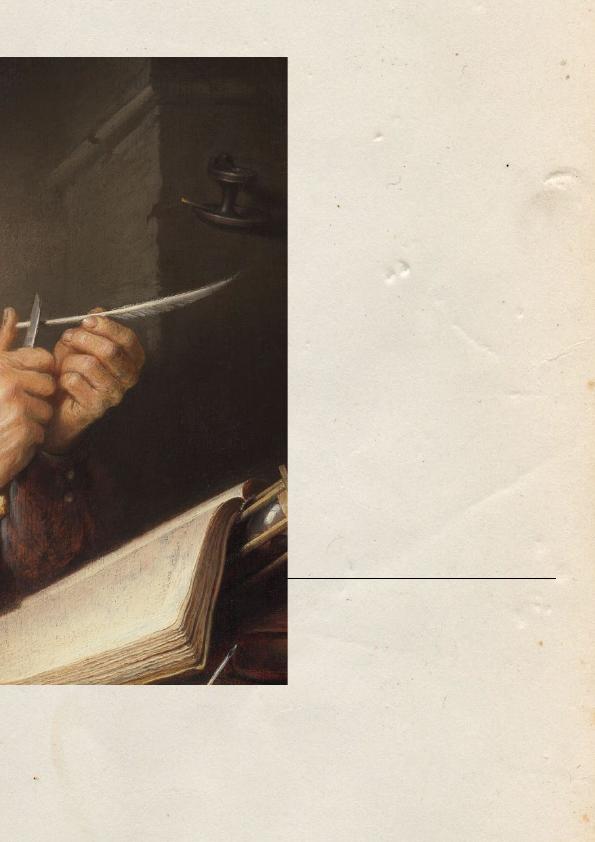

A man carving or sharpening

a quill for writing. Quills

are made of keratin - the

same stuff that makes up your

ngernails.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

17

HISTORY

A Work of Art:

Illuminated Manuscripts

by Shahan Cheong

O

ne of the most

enduring

images of the

history of writing

is the illuminated

manuscript!

A manuscript is a text

written entirely by

hand. An illuminated

manuscript is such a text

which has been created

with precision and care,

and which has then

been illustrated and

decorated (‘illuminated’)

by an artist.

Illuminated

manuscripts were like

the magazines of the

Middle Ages. Just like

a modern magazine,

the pages were bright,

vivid, overflowing with

colours and gaudy

images, and the letters

were all outlined and

emboldened with vivid

reds, blues, greens and

even gold!

Illuminated

manuscripts were

extremely expensive.

Dyes and pigments to

make the paints and

inks necessary could

be hard to find. The

quills required for even

a relatively simple

piece were likely to

be numerous. In much

the same way that a

professional painter

uses several types of

brushes to achieve

different effects, an

illuminator or scribe

had a variety of quills,

all cut to different

angles and shapes, to

give a range of lines

and writing styles.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

20

Writing at this time

was a true art-form, but

it could be incredibly

slow. Even writing a

single letter or a few

words could take a

long time. But then,

when you were writing

on one of the most

expensive surfaces

ever imagined…you

wouldn’t want to make

a mistake! Illuminated

manuscripts were

written and decorated

on sheets of vellum –

basically, really really

thin sheets of leather.

Specifically, calfskin

leather.

Cows and calves were

hard to come by. As

the animals were more

important alive than

dead, few people were

willing to butcher an

animal purely to get its

skin to write on! On top

of that, each calf would

only yield enough skin

for a few pages.

It’s for all

these reasons

that illuminated

manuscripts were

usually private

commissions. A

manuscript which was

to be prepared and

illuminated would

probably be something

important – a gift to a

wealthy or powerful

person. An important

religious text, a historic

document or an

important record.

An illuminated bible from 1407.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

21

HISTORY

Writing for a New Age:

The Industrial Revolution

by Shahan Cheong

B

y the 1600s, more and more people were learning how to

write. It’s estimated that approximately 25% of people in

Britain at the time knew how to read and write. The printing

press, and universities and schools established in the Middle Ages

meant that slowly but surely, the ability to write was being spread to

more and more people. However, despite this spread of knowledge,

the ability to practice this knowledge remained frustratingly slow!

For centuries, quills remained the writing instrument of

choice. Nobody had figured out a way of making a

better pen. It remained this way until at least the

latter half of the 1700s, when the first finicky,

fiddly, handmade metal pens, manufactured out

of pressed steel, were created.

Modelled on the points of quills, these steel

pens had various advantages over the quill. You

didn’t have to keep sharpening it. You didn’t

have to keep cutting new points. But on the

ip-side of the coin, they could wear out and

rust. The inks used could be corrosive, and

would eat away at the metal, making the

points brittle and prone to breakage.

Some people did try to make these pen-points

out of gold, but they were often too expensive

and finicky. It wasn’t until the 1800s, when the

Industrial Revolution had been going for a while,

that the next big step in writing was made!

Mass-produced steel pens could be made swiftly and easily using

simple punch-presses. Thousands could be produced in a day.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

22

Mass Produced Writing: The Steel Pen

In a quest to nd something better for writing

than the nicky quill, further experiments were

made in the manufacturing of steel pens. The

breakthrough was made in the early 1820s, with

brothers John and William Mitchell.

Prior to the Mitchell brothers, metal pens had

been laboriously cut and bent and shaped by

hand. A frustrating, finicky, fiddly business that

took ages. The Mitchells realised that if they had

the right thickness of metal and the right cutting

tools, they could use a die or a mould to punch

out hundreds…thousands…of pens! The phrase

‘cookie-cutter’ comes to mind.

Using punch-presses, the Mitchells could crank

out thousands of cheap, identical steel pens

all with a few pulls of a lever! Every single pen

would be identical, and they

could produce as many of

them as they

wanted to!

Once they

had perfected

their mass-

production

techniques,

all they had

to do was

package

the pens in

little boxes

(say 100 pens

for 6d), slap a

label on it, stack up hundreds of these

little cardboard boxes and send them off

to stationery shops all over the world!

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

23

HISTORY

The steel pen caused a revolution

in writing! Although some people

continued to use quills, the fact of

the matter was that the steel pen

was just…better! You didn’t have

to make it yourself, it was cheap, if

it rusted, you threw it out and got

another one, it could be bought in

bulk, and it came in a wide variety

of points for almost any type of

writing! Writing was starting to

speed up!

Along with these newfangled

metal pens came new styles of

writing. Scripts like Spencerian,

Roundhand and Copperplate became

more popular. Without having to

stop and sharpen pen points all the

time, a person could concentrate

more on practical, high-speed

cursive handwriting, instead of

painstakingly writing every single

stroke with a fragile, hand-cut quill.

The steel pen copied more than

just the shape of the quill pen

(which itself had been copied

from the shape of the reed pens

of ancient times), it also copied

some of its physical characteristics

– Steel pens of the 1800s were

manufactured out of thin sheets of

springy steel. This allowed the pen

to flex and bend when it wrote.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

24

The tines (the two halves of the

pen-point) would flex and spread

as more pressure was added to it,

creating a thicker line, and would

spring back together when pressure

was reduced, to create a thinner

line. It’s this property of steel pens

(and the quills which came before

them), that allowed for the thick-

thin variations in lettering that were

common in manuscripts of all kinds

during the 18th and 19th centuries.

Artisan Instruments:

Glass Dip Pens!

Rivalling the steel pen and the

quill for about 200 years was

another type of writing instrument.

Almost forgotten today, they’re

actually still very popular, still

manufactured, and you can still buy

them! And they’re still made in the

same city where they were invented,

back in the 17th century.

The glass dip-pen!

For centuries, Venice, Italy has

been the centre for the manufacture

of beautiful pieces of artistic

glasswork. Everything from purely

decorative items, to candleholders,

Glass dip-pens are still manufactured today at

the famous Murano Glassworks in Venice, Italy.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

25

HISTORY

drinkware, bottles, vases, decanters

and countless other items made

of shimmering, hand-blown, hand-

shaped, multi-coloured glass!

One of the items turned out by the

famous glassmakers of what was then

the Venetian city state, was the glass

dip pen!

Manufactured out of one or two

rods of glass, which could be crystal

clear, or which could be dierent

colours (to make it more beautiful),

these pens were painstakingly heated,

melted, turned, stretched and coiled

by hand, using simple tools and the

glassmaker’s own judgement. The

result was a pen, from writing tip to

the end of the shaft, made entirely out

of what would become…a single piece

of glass!

Glass pens of course, lacked the

exible writing nature of quills and

steel pens, but their advantages

were that they were beautiful,

individual, easy to clean, excellent

for basic writing, and they wrote with

unsurpassed smoothness!...as smooth

as glass!

Glass pens also had another

advantage over quills, and even the

steel pens which replaced them – they

could write for longer!

The grooves in the tips of glass pens

could hold much more ink than the

underside of a steel pen, or the hollow

interior of a goose-feather quill. While

a single dip of ink using a quill or steel

pen might get you two or three lines

of script at most, a glass dip pen in one

dip in the inkwell, might give you the

better part of one or two paragraphs!

Why, you might ask, then, weren’t

glass pens immediately used to replace

quills, instead of going onto steel pens?

The simple reason is…money.

Glass pens were (and still are)

handmade artisan pieces. It would

be impractical to try and supply the

whole world with delicate, nely

turned glass writing instruments. A

quick and cheap steel pen, cranked

through a hand-operated punch-press

was much more convenient. And with

schools and universities growing in

prominence in the 1700s and 1800s,

speed and eciency was the order of

the day!

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

26

Writing for

the Common Man

by Shahan Cheong

By the 1800s, literacy was growing ever faster. New mechanical printing

presses, popular novels, newspapers, pamphlets, magazines, brochures

and literary journals were all increasing the amount of materials that one

could hope to read, as well as showing just what could be written about!

In previous times, little progress had been made with writing instruments

because not enough people did enough writing for any serious progress

to be necessary. By the Victorian era, with so much to read about and write

about, advances in writing technology were kind of important!

Handmade glass pens were too expensive and slow to produce in

any signicant quantity for everyday writing (and they were fragile!),

so instead, metal pens took the lead. Handmade at rst, they were

replaced in the 1820s by the rst machine-made, mass-produced steel

pens! The vast majority of steel pens were manufactured in their

millions by a variety of makers operating in the Jewellery

Quarter of Birmingham, in England.

The vast majority of these pens were

made of cheap sheet steel. They were

designed to be written with

until they wore out,

and then simply

discarded and

replaced. Depending

on how much writing

you did, and how well you

looked after a pen-point, it

could last a surprisingly long

time. Weeks or months or

more before it had to be replaced.

More expensive pen-holders were made

of lathe-turned wood with gilt brass

ferrules. The upper-end of cheap.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

28

Some pens were made of gold. Not just because gold looks pretty and

it’s expensive, but because gold doesn’t rust! Properly formed with a tip of

hard, wear-resistant metal welded onto the point, a gold pen could write

almost indenitely.

Steel Pens and Pen-Holders: From Simplicity to Elegance

From ancient times to the 1800s, a ‘pen’ had been an instrument for

writing or drawing using ink. But what happens when your ‘pen’ is no

longer a long, sti reed, or a hand-cut goose-feather quill? What happens

when your ‘pen’…

your writing

instrument…is a tiny

little steel object, just

under two

inches (about

4.5cm) in

length? How on

earth are you going

to write with something so

small without covering your ngers

in ink?

Well, to make writing with such a tiny object

practical, you would need something to set the pen into

while you were using it! A holder of some sort, and during the

Victorian era, a wide variety of pen-holders for steel dip-pens were

available. However, here it's important to make a distinction.

Today, the entire setup would simply be called a ‘dip pen’, but back in

Victorian times, only the throwaway steel point was called a ‘pen’ (what

today, we’d call a ‘nib’). The shafts into which these pens were inserted,

and which the writer held in his or her hand, were called pen-holders.

Pen-holders, unlike the disposable, uniform, mass-produced steel pens,

varied signicantly in quality and style. They ranged from bog standard,

simple wooden ones, which were almost as cheap as the pens tted into

them, to elegant shafts made of precious metals and materials, which

might be sold in boxed sets.

More expensive pen-holders were made

of lathe-turned wood with gilt brass

ferrules. The upper-end of cheap.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

29

HISTORY

Institutions such as

schools and universities,

where much writing

likely had to be done on

a budget, the cheapest,

simplest wooden pen-

holders with pressed steel

ferrules were used. Places

with a higher standing, such

as banks, libraries, post-

oces or hotels might have

nicer pen-holders laying

across their desks, to reect

the status of the people who

might use them. Lathe-turned

wooden holders, stained and

polished, with handsome

brass ferrules might be found

here. They would last longer

with the treated wood nish,

and brass wouldn’t rust if it got

into contact with the liquid ink

used at the time.

At the top end of the scale

were pen-holders made of bone,

brass, silver, gold, ivory, and

Mother of Pearl. Holders like

this would come in handsome

presentation boxes and carry-

cases, similar to those used

to transport jewellery. They

were manufactured by famous

stationers, silversmiths, and jewellers

and were available only for the

seriously wealthy! A person owning

such a set might receive it as a

present, a reward, or it may come as

part of a set of something larger (such

as a writing slope).

Pen-holders used in

schools and public

institutions were often

mass-produced, no-

frills wood-and-pressed

steel affairs.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

30

Pen-Holder and Propelling

Pencil Set. Sterling Silver

and Ivory. Manufactured in

London in 1901 by jewelry

rm Mappin & Webb.

Sterling Silver Pen Holder and Propelling Pencil set. Manufactured by

Sampson Mordan & Co. Ca. 1880, with original silk and velvet-lined

presentation case.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

31

HISTORY

Mechanical Writing:

The Typewriter!

One of the biggest problems faced

by man through the entire history of

writing was the problem of speed.

With reed pens and quills, writing

quickly had not been possible. The

fragile nature of these natural writing

instruments meant that they were

prone to breakage if used under heavy

pressure. The elaborate scripts of the

time were impossible to write with any

serious speed. In the 1800s, with the

development of the cheap, throwaway

steel pen, which was capable of taking

the heavier pressure of faster writing,

styles like Spencerian were developed,

which were neater, easier to read, and

much faster to write.

But the problem with all these

writing systems, regardless of their

merits, was that they could only go

as fast as a person could write, which

in most cases was not very fast, even

with fancy cursive script! To advance

writing even further, what if there was

a machine which could write for you?

Surely it would be faster, neater and

much less tiring?

In the 1450s, the rst step was

made: the printing press featuring a

press-bed lled with little pieces of

movable type, cast out of metal. Hard-

wearing, reusable, and which could

be set into any arrangement, these

made books, pamphlets, magazines

and other written material far more

accessible to the common man. While

the printing press put the scribes

out of business, they didn’t solve the

problem of speeding up writing. It

was still done with a quill or a steel

pen, and an inkwell.

Eorts to create a writing machine of

some kind have been around almost as

long as writing itself, but few people

had gured out a way of producing a

machine that worked well enough to

produce neat, legible text beyond a

printing press. Several machines were

invented during the second half of the

1800s, but few were practical enough

to be mass-produced.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

32

In 1865, Rasmus Malling-Hansen

created the “Hansen Typing Ball”,

arguably the world’s first ‘type-

writer’, in that it used movable type

(similar to that found in printing

presses) to write on sheets of paper

(hence ‘typewriter’). The typing

ball was novel, but not especially

practical. Hansen had hit on the

key aspect of a typewriter – the

paper moves while the keys stay

put, but beyond that, he was

rather lost. He hadn’t figured out

how to switch between upper and

lowercase characters, and it was

nearly impossible to see what was

being typed, because the typing

mechanism was in the way! Although

it was commercially produced, it was

never especially successful.

The rst typewriter of a kind we

might recognise today, came out in

1876, and was the brainchild of three

men: Christopher Latham Sholes,

Samuel W. Soule, and Carlos Glidden.

They gured out a more practical

arrangement for what would become

the keyboard. They determined how

the cylinder holding the paper should

move back and forth. They even came

up with the QWERTY keyboard that

we still have today! But they lacked

the money to get the machine o the

ground. So, they sold the idea to a

company called Remington, famous for

making rearms (heard of Remington

ries? Yeah, they made those).

The 1870s and 80s was a boom

time for (sometimes whacky, and

useless) inventions, but the folks at

Remington were looking for ways to

branch out from rearms. They were

already experimenting with sewing

machines. Why not a writing machine?

They bought the idea, and created the

world’s rst practical typewriter – the

Remington Model 1. For the rst time

in history, a person could produce neat

writing faster than a scribe, and more

immediately than a printing press! For

the next century, the typewriter would

be the go-to machine for high-speed

word-production.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

33

HISTORY

Writing for

a New Century

by Shahan Cheong

In the 1450s, Johannes Gutenberg

created the movable-type printing

press, speeding up the production of

written material.

In 1876, three Americans created

the typewriter, speeding up word-

processing.

In 1880, people were still writing

using steel dip-pens and holders,

and hand-cut goose-feather quills.

Writing instruments which, in

essence, had not changed since the

times of antiquity.

Although writing styles had

changed, in an effort to make

writing easier to read, and faster to

produce, a fundamental problem still

remained in the world of writing.

That of portability.

Every pen up to this point had

been a ‘dip pen’. Reeds, quills and

steel pens all had to be dipped in

a separate inkwell or ink bottle

before they could be written with,

and every reed, quill and steel pen

had to be re-dipped in ink every

few words, over, and over, and over

again. Countless trillions of dips

throughout history, used to write

everything from the Bible to the

works of Charles Dickens.

Efforts to create a pen which did

not have to be re-inked every two

lines date back centuries, all with

limited success, and none which

ever entered mass-production. In

the 1800s, clip-on reservoirs were

sold, which would allow a dip-pen to

write longer with slightly more ink in

the pen-point, held there by surface-

tension, but these would only

extend dips from every two lines, to

every paragraph or two, at best.

The Reservoir Pen

The first steps in producing a pen

which could be carried around in

one’s pocket, and which had its own

in-built ink-supply came about in

the 1880s. And it even has its own

legend.

If you believe such things, the story

goes that two men get together for a

business-meeting. One presents the

other with a contract to be signed,

and an early reservoir pen, with which

to sign on the dotted line. At the

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

34

crucial moment, the pen malfunctions,

leaking horrendously and dribbling

black ink all over the contract, ruining

it! By the time the rst man had found

another copy of the document, and

another pen, his client had packed up

and left, to sign his name o to one of

his competitors!

Infuriated by this turn of events,

our young man locks himself away

in a shed and furiously works day

and night until he creates the ideal,

leak-proof reservoir pen! The first

of its kind in the world! He founds

a company, and goes on to create

millions of what today, people call

‘fountain pens’!

The name of this man is Lewis

Edson Waterman.

True?

Well, Lewis Edson Waterman was

definitely a real person, that’s for

sure. But the fanciful origin story

of how he created one of the oldest

writing-instrument companies

in the world, is not! No-where is

this story supported in fact! Not

even the Waterman Pen Company

itself believes it to be true! Lewis

Waterman didn’t invent the fountain

pen, just like how Henry Ford

didn’t invent the motor car, nor

Isaac Singer, the sewing machine.

Waterman, like Ford and Singer,

merely did something, or invented

something, which made the creation

they tackled, more accessible to

more people!

In the case of Waterman, he invented

the three-channel capillary feed.

The big problem with early

fountain pens was that…they

leaked…very badly. Nobody had

figured out how to store ink in a

pen-barrel, and have it drain to

the gold pen point in a controlled

manner which allowed for smooth,

comfortable writing. The ink stored

inside a fountain pen will last

for weeks, maybe even months,

depending on the usage of the pen!

But the pen is useless if the ink

doesn’t flow, or if the ink flows too

freely, which were the big problems

facing early pen-makers. It’s for this

reason that it wasn’t until the late

19th century that a pen with its own,

in-built ink-supply was a possibility!

The basic operation of a fountain

pen can be best described as a

controlled leak. Ink leaks out of the

reservoir, down the feed, through

the nib, to the point, onto the paper.

But the problem with early fountain

pens was that the manufacturers

didn’t understand how this worked.

They didn’t realise that as ink leaves

the pen, air needs to replace the ink,

to balance out the pressure inside

the pen with the pressure outside

the pen!

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

35

HISTORY

Anyone who’s ever punctured a

can of liquid (like condensed milk

or similar) and tried to empty the

contents of the can through that

one tiny hole they made, will know

how difficult it is. The fluid glops

and slops and flops out all over the

place, it’s very slow-draining and

it takes forever to empty. This is

what early fountain pens were like!

The result was huge blotches of ink

being spat out onto the paper, a

disaster! But, if you punch another

hole in the can, the fluid comes

out much faster. This is because air

is rushing in one hole while fluid

rushes out the other, balancing out

the pressure.

Early Fountain Pens

The golden age of fountain

pens ran from the 1900s to the

1950s. It was during this time

that there were literally dozens of

competing companies, all vying

for public attention with new

designs, new styles, better filling

mechanisms and improved writing

characteristics. Owning a fountain

pen – a significant investment in

those days – was considered a

status symbol! But they were not

embraced everywhere.

Institutions like banks, post-offices

and schools continued for many

decades, to use old-fashioned steel

dip-pens. One of the reasons was

cost! Fountain pens were expensive!

Dip-pens were dozens for a few

cents, whereas a fountain pen could

cost dollars! Even in the 1920s and

30s, some schools continued to

teach penmanship, and conduct

standard lessons using

old-fashioned steel

dip-pens and

inkwells,

Waterman’s three-channel capillary

feed allowed the ink in fountain

pens to ow out smoothly, and also

allowed air to ow in at the same

time. For the rst time, this produced

a smooth-writing fountain pen! The

next chapter in the history of writing

instruments could now be written!

which had to be

filled by the class ink-

monitor – a child selected

for this task by the teacher.

Roald Dahl, the famous

children’s author, recalled how

fountain pens were banned in

school and students had to rely

One of the rst attempts at

creating a smooth-operating

fountain pen was the 'double-

feed', shown here on this

antique Swan eyedropper pen

from the 1890s.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

36

on dip-pens. Anne Frank recalled her

joy at being given a fountain pen for

her birthday by her grandmother,

and taking it proudly to school for

the first time! In her own words,

she said: “Me! The proud owner of a

fountain pen!”

Early fountain pens were unlike

almost any which are manufactured

today. For one, there was a much

greater variety of styles to choose

from. Not just in how the pen looked,

but how it filled, how it wrote, the

type of line it produced…and even

how flexible the nib was!

Selling pens to people who had

grown up using quills and exible

steel dip-pens meant catering to their

writing expectations. Early fountain

pens were sold with ‘exible’ nibs,

which bent and spread according to

the writer’s pressure on the point.

This allowed people to continue

using the cursive writing-styles

which they’d grown up with. Pens

with exible nibs faded away in the

postwar decades and are now quite

rare in modern pens.

The majority of old-fashioned

fountain pens were ‘straight sac’

fillers, where the interior of the

barrel housed a rubber ink-sac,

and a flexible steel pressure-bar.

Operating the filling mechanism

pressed down the bar, flattening the

sac and forcing out the air. Releasing

the filling mechanism created a

vacuum which sucked in ink.

Modern fountain pens almost

exclusively use converters (little

pumps) or ink-cartridges to supply

ink to the pen, although there are a

few companies around today, which

still produce old-fashioned sac-

filling fountain pens as they did back

in the 1920s.

Selling reusable

pocket pens to a

society which for

a hundred years,

had used throwaway

stamp-cut dip-pens,

was challenging.

The original

packaging for

this 1904 Waterman

clearly states: "DO

NOT REMOVE GOLD NIB

FROM THE HOLDER", a

common practice of

the time.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

37

HISTORY

The Ballpoint Pen

Fountain pens solved a lot of the

problems which people had with

writing instruments up until that point.

They could write for a long period

of time without wearing out, they

could last almost indenitely, if well-

maintained, and they didn’t leak! But

they still had an Achilles Heel.

Fountain pens, like the steel pen,

quill and reed before it, use liquid,

water-based ink. This smudges if it’s

not been given enough time to dry

properly. Anyone reading this who’s

ever spoken to their parents or

grandparents, and were told stories

of kids being smacked across their

knuckles in school, and being forced

to write with their right hands,

instead of their left hands…will

probably wonder…why?

The reason is that left-handed

writers smear ink across the page

as they write! Training kids to write

right-handedly was a way to prevent

this, back in the days of widespread

dip-pen and fountain pen use. For

centuries, blotting-paper was used

to hasten slow-drying ink, but one

man who found the smudging and

smearing of ink too frustrating, and

who couldn’t use blotting-paper

repeatedly in his work, was to try

and find a way out of this inky,

black-stained mess!

His name is now legendary: Laszlo

Jozsef Biro.

Biro was a Hungarian journalist

in the 1920s. He noticed that the

thick ink used to ink the printing-

plates on presses dried quickly

after newspapers had been printed.

It was no-longer necessary to iron

newspapers at home to dry out the

previously-used, slower-drying ink

(anyone who’s watched the first

episode of ‘Downton Abbey’ will

remember this!).

Introduced in 1921, and for sale at the exorbitant price of $7.00 (!),

the button-ller Parker Duofold was one of the most famous pens of the

Golden Age of Fountain Pens. A Duofold was used to sign the Japanese

surrender in 1945. Arthur Conan Doyle wrote his Sherlock Holmes stories

with one. The pen in this picture dates to 1928.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

38

Biro was fed up of having to blow

on fountain pen ink, or use blotting-

paper, to dry his writing. He tried

putting printer’s ink into his fountain

pen to see what would happen! It

was a disaster. The ink was too thick

and his pen clogged up, becoming

thoroughly useless!

With his brother Gyorgy, a chemist,

the Biros struggled to come up with

a pen that could use thicker, faster-

drying ink than the fluid inks used in

fountain pens at the time. In 1938,

they filed for patents in France and

England for their new ball-point pen!

The future might’ve looked bright

for the Biro brothers, if the Nazis

hadn’t come to power…

When the Second World War started

in 1939, the Biros were in hot water.

As Hungarian Jews, they were on the

black-list of people that the Nazis

were actively hunting down. Together

with a friend, they managed to sneak

out of Hungary in 1941, and escape

all the way to Argentina in South

America. Here, they led another

patent in 1943. Among the rst

people to use the newfangled ‘ball-

point’ pens were pilots!

Pilots of the Argentine and British

air forces (the RAF) were given the

new pen so that they could write

notes in their log-books at high-

altitudes, in aircraft which were

often unpressurised. Air-pressure

is what makes fountain pens work.

The differences in air-pressures at

high altitudes meant that they were

susceptible to leaking horribly when

taken up in an aircraft!

In the postwar era of the 1950s

and 60s, ballpoint pens started

rivalling fountain pens. Ballpoint

pens are cheaper to produce, lower

maintenance and didn’t leak as

badly as fountain pens if things went

wrong. This made them popular. The

main downside of ballpoint pens

are the harder writing-pressures

required to make it work. This makes

them unsuitable for some people,

who stick to fountain pens for

smoother, lighter-pressure writing.

To pilots, ballpoint pens seemed like

a lifesaver, a godsend in writing, but

not everyone embraced ballpoints

when they first came out! Novelist

Graham Greene famously said that

ballpoint pens were useless for

everything apart from filling out

forms while on board an airplane!

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

39

HISTORY

Graphite and Rubber:

A History of Pencils

by Shahan Cheong

F

or much of history, pens

were unreliable. They leaked,

they dribbled, they required

sharpening, cutting, replacing,

repairing…all in all, not the most

ideal of writing instruments.

What if there was an alternative to

the pen?

For a long time, there wasn’t, until

the mid-1500s.

Graphite, the material found in every

pencil in the world, has been known

about for millennia, but it wasn’t until

the early 1500s, when large deposits of

graphite were found in England, that it

was rst used for writing. Graphite is a

soft, crumbly rock. It leaves nasty grey

streaks on the hands, but shepherds

living in Cumbria, where the graphite

was discovered, realised that if you

wrapped it up in cloth and exposed

a point, it made a crude writing

instrument. They used these chunks of

graphite to mark their sheep, so that

they would know how many they had,

and to whom they belonged.

Due to graphite’s dark grey colour,

it was sometimes called ‘black

lead’ or the Latin-sounding name

‘plumbago’, similar to the actual

metal lead (‘Plumbum’). For some,

the similarities were too much, and

confusion between graphite and

lead caused one man, Abraham G.

Werner, a German geologist, to coin

the term ‘graphite’ for this material,

from the Greek words ‘Graphos’

(writing) , and ‘ite’, indicating a rock

or mineral.

The First Pencils

The problem with graphite is

that it’s very soft. It crumbles very

easily. This means that it’s almost

impossible to carve it or shape it

with ease, or make it small enough

and thin enough to make a practical

writing instrument, at least, not on

its own.

In 1789, French painter Nicolas-

Jacques Conte (1755-1805) invented

the modern pencil.

At the time, France was at war

with Britain because of the French

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

42

Revolution. With a British naval

blockade, there was a serious

shortage of British graphite in

France, and only low-grade French

graphite to fill in the gaps. The

inferior graphite was impossible to

write with because of its crumbly

nature. Conte got the idea of

using this crumbly nature to his

advantage. He crushed graphite

until it was powder, then mixed the

graphite with clay. The clay gave

the graphite the strength that it

required to stay together. It also

allowed the graphite-clay mixture

to be mixed and formed into rods,

which could then be fired in a kiln

to create graphite sticks which were

soft enough to write with, but hard

enough not to shatter prematurely.

By mixing the ratios of clay and

graphite, Conte realised he could

produce different levels of hardness

in his graphite rods. He encased

the finished rods in wood, giving us

the modern pencil, as well as the

different grades of graphite which

come with them.

Mechanical Pencils

The pencil sharpener as we know

it today was not invented until

1847, by Thierry des Estivaux, a

Frenchman. Prior to Monsieur des

Estivaux’s invention, pencils had

to be sharpened by whittling them

down with a pen-knife. This was a

fiddly and imprecise method at best,

which could damage or break off the

graphite point, necessitating further

sharpening, all over again!

What if it were possible to create

a pencil which did not have to be

sharpened? A pencil which could

be carried around in one’s pocket

and which would always have more

graphite stored inside it in case the

tip wore down? And what if, when

that store of graphite was depleted,

instead of throwing out the pencil,

you could just refill it? The pencil

would be long-lasting, and you could

use every last bit of graphite in it,

instead of wasting those few bits at

the end.

Such an invention would surely be

called a mechanical pencil!

With the knowledge of how to create

reliable graphite rods now in place

in Britain, Europe and the United

States, a person who could invent a

superior pencil which did not have to

be sharpened constantly could make

himself a tidy sum of money.

That person was an English

silversmith named Sampson Mordan

(1790-1843).

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

43

HISTORY

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

44

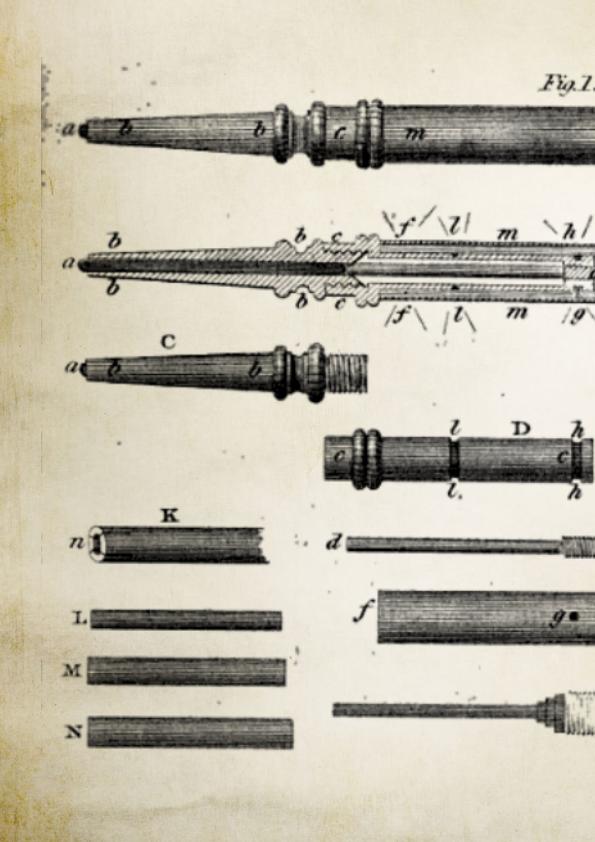

Sampson Mordan's patented propelling pencil, from 1822.

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

45

HISTORY

Mordan observed that pencil-holders

in the early 1800s did just that. They

held the pencil…and did absolutely

nothing else. You still had to sharpen

it. You still had to advance the pencil

whenever it got too short, and it just

wasn’t a practical method of using a

pencil at all!

What if you could eliminate the need

to sharpen the pencil altogether? Why

not just have the graphite rod housed

inside a holder? That might work…but

then, how do you advance the graphite

when it gets worn down?

To overcome this issue, Mr. Mordan

developed what was called the

‘propelling pencil’, the world’s rst

kind of mechanical pencil.

Mordan-style propelling pencils

were made of metal, and could be

unscrewed at the tip. A graphite rod of

the correct diameter and length was

then inserted into the pencil and the

tip was screwed back down.

Twisting the pencil-tip advanced

the feed mechanism inside the pencil

which pushed or ‘propelled’ the

graphite shaft forward, through the

opening in the pencil tip, allowing a

person to write. Once the graphite

wore down, it was simply a matter of

twisting the pencil again to expose

more graphite, over and over until

the graphite was gone. Then pulling

the pencil apart and inserting more

graphite when it was empty.

Cheaper propelling pencils were

made of brass, or Nickel Silver. More

expensive pencils were made of

sterling silver, or solid gold! Just as

how novelty pens can be found in

any cheap souvenir shop today, in the

1800s, some pencil manufacturers

turned out all kinds of novelty

propelling pencils! Pencils could

look like almost anything! Revolvers,

baseball bats, cricket bats, telescopes,

walking-sticks, wine bottles…and

they could operate in almost any way

imaginable – twist-feed, drop-feed,

ring slide…the varieties were almost

endless! Some pencils came with

inbuilt dip-pens, some came with

stones or seals set into the ends where

the owner’s initials could be engraved,

for sealing letters with wax, some came

with rings set into them, so that they

could be attached to a gentleman’s

watch-chain, or to a lady’s chatelaine.

Modern ratchet-and-clutch style

pencils, which use graphite rods in

fractions of millimetres, (0.3, 0.5,

0.7, etc), and which advance these

rods through the pencils with a

simple click, were invented in the

1930s. Developments in America and

Japan advanced pencil technology

signicantly, and for a while, there

were two rival systems to propel

the graphite through the pencil: the

ratchet mechanism as used in the

‘States, and the more old-fashioned

twisting mechanism, used in Japan,

but in the end, the ratchet-click

mechanism won out, because it was so

much easier to operate with one hand.

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

46

Conclusion

by Shahan Cheong

From cuneiform to cursive script, from

fancy feathers to sleek modern writing

instruments, I hope you enjoyed this write-

up on the history of writing and writing

instruments! But, from writing, what about

reading? Next month, we’ll be looking at

the history of books! Where they came from,

how they were made, and famous books which

have made, and/or influenced history,

science, literature and any other number

of subjects by their creation!

Shahan Cheong

Editor

TAT History

The images used in this issue of TAT History came from

public domain websites, Wikimedia Commons, or else

were photographs taken by the TAT History Editor.

Information for this issue of TAT History came from the following sources…

Pictures used in this issue of TAT History came from Wikimedia Commons, were taken by the

TAT History Editor.

Sources used in this issue of TAT History included…

http://www.penhero.com/ - PenHero.com (Accessed 20th of May, 2015)

Documentary: “Illuminations – Treasures of the Middle Ages” (BBC. 2005)

Documentary: “Alphabet – e Story of Writing”. Presented by Donald Jackson

Documentary: “e 26 Old Characters”. Presented by the Sheaer Pen Company (1947).

http://www.ancient.eu/cuneiform/ - e Ancient History Encyclopaedia (Accessed 15th of May,

2015)

THE

AUSTRALIA

TIMES

®

Independent Media Inspiring Minds

52

DONATE NOW

makeawish.org.au 1800 032 260

Liam, 6, diagnosed with large cell lymphoma,

wished to go to a diamond mine.

They create hope for the future, strength to battle life-threatening illness and

joy from their unique once in a lifetime wish experience. Help us unleash the

incredible power of wishes by donating today!

To seriously ill children

around Australia, wishes

are powerful.

C

M

Y

CM

MY

CY

CMY

K

Make-A-Wish Advertisement FA.pdf 1 4/09/14 12:41 PM